Coming Home to Coal Country

A young environmentalist faces her roots

May 11, 2016

Ashley Funk looks back fondly on her days of playing in the black hills behind her Southwestern Pennsylvania house. But when she learned more about what those black hills were made of, it drove a wedge between her and her hometown.

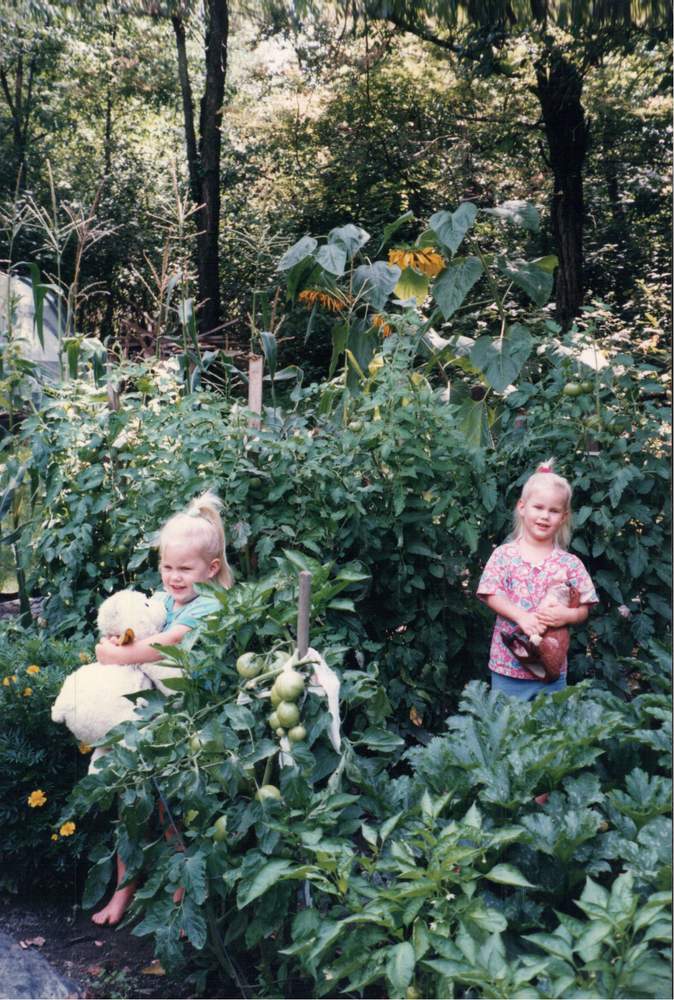

When Ashley was a young girl the family lived in a house that had huge piles of dark dust behind it.

“You kind of just see this expanse of black,”

she said.

The piles were a really fun place to play. Funk and her twin sister would go out there and build things kind of like sand castles. They would come inside with the dust in their hair, on their hands and around their eyes. They didn’t know how dangerous it was.

Funk was born in Westmoreland County, Pa. in a hospital named for a famous coal man: Henry Clay Frick. Frick had made his fortune and died long before Funk was born, but his name still adorned Frick hospital, as well as two streets in the town she’d call home--Mount Pleasant, Pa. The town had been built on coal.

An environmental awakening

As a child Funk knew she wanted to go to college, and by middle school she was already worrying about how to pay for it.

“When I was in 8th grade, I was watching Gilmore Girls,” she said. One of the characters on the television show tried to get into Harvard, and another character told her that she should volunteer.

“That’s when I realized, ‘Oh my god, I have to volunteer to get into college,’” she said. “That strangely started my volunteerism.”

Funk, who was then 14, gathered a group of Mount Pleasant kids together to pick up trash on the side of the road.

“We called it Pollution Patrol,” she said. The motto was “Making a mount more pleasant, piece by piece.”

People in the town donated bags and gloves, and would sometimes even stop their cars to thank Funk and the kids for their work.

That next summer, Funk went to a science camp that was sponsored by NASA. Because her family was low-income, it was all paid for, and every kid got to choose a focus area to study. Funk chose the environment and climate change.

Little by little, Funk’s interest in science and the environment grew. The two interests came together into one overwhelming obsession: climate change.

The Lawsuit

It was around this time that Funk found out the black dust she and her siblings played in as children wasn’t safe. In fact, it might have been a carcinogen.

“I think my first reaction was, I wonder what age I’m going to get cancer,” she said.

Funk was angry at the old mining companies, like H.C. Frick, that hadn’t cleaned up the mess they made. She was angry at the state for letting the piles sit for so long.

Funk, the child of a coal-industry town, started talking more and more about sustainability, carbon emissions, and the problems with energy companies. A national environmental group called Our Children's Trust heard about her and reached out.

The group works with young people to participate in lawsuits over climate change. They help young people sue the government on the grounds that children have a human right to a healthy environment when they grow up. Funk became a plaintiff in an Our Children’s Trust lawsuit against the state of Pennsylvania over its carbon emissions. If they won, Pennsylvania would be forced to limit those carbon emissions.

“I didn’t tell anyone I was doing it,” she said. “I just did it. I went downstairs and said, ‘Mom, can you sign these papers for me. You have to sign them because I am a minor but I’m filing this lawsuit.’ And my mom was like, ‘Okay.’”

At first, Funk just kind of assumed she could keep this whole court case quiet. She knew a lot of people in town, and she knew some of them wouldn’t approve of it.

“I didn’t tell my dad for a while,” she said. “He very strongly did not believe in climate change.”

It’s particularly hard for some people in Southwestern Pennsylvania to imagine a world without fossil fuels because, even though the coal industry is mostly gone, the region is still dependent on fossil fuel extraction in the form of fracking and natural gas wells.

The lawsuit was filed in 2012 and made a multi-year trip through the court system. In the end Funk and Our Children’s Trust lost the suit. But it got the attention of the coal companies, the state, and of course, the people of Mount Pleasant.

Leaving home

Pretty soon, in the same town where people used to stop and thank Funk for picking up litter, people were calling her a hypocrite. The most hurtful insults were posted online, she said. Comments were left in the comment sections of online newspaper articles about the case, calling Funk and the environmental lawyers fools, idiots and worthless human beings. Comments like, “Congratulations on eliminating over 500 jobs and putting yet another dent in the SWPA economy.”

The tension was stressful and Funk felt like she didn’t belong in Mount Pleasant anymore. As her high school years were coming to a close, she couldn’t wait to leave the small town behind her. She applied to college and got into prestigious Wellesley College. It was a radical departure from the place where she had grown up--exactly what she was looking for.

“I went through this really long process of trying to get rid of my accent, trying to get rid of phrases [that are] common in my area,” she said.

Funk overemphasized the use of proper grammar and big vocabulary words. “Friends were like, ‘Ashley, stop being so smart. You’re making an idiot out of yourself.’”

When she went to college, she figured she’d escaped Mount Pleasant forever. She thought she’d find people like herself. She would start a new chapter, join a new tribe.

She got to Wellesley in the fall of 2012 and declared her major, Environmental Studies. Funk’s outgoing, so making friends wasn’t hard. She joined other students for the Keystone Pipeline protests and during school breaks, she traveled for environmental field research.

But something was off. The closer she got to her adopted tribe, the less and less they felt like her people. She remembers one class she took her freshman year, called Wealth and Poverty. All the students kept talking about “them.” Like, this is how people feel when they’re on food stamps.

“As if they’re not in the room,” she explained. But Funk was in the room, and her family had been on food stamps.

“I remember getting so frustrated. Either the professor or someone in class would say something completely wrong. One time it was, like, ‘You can’t buy soda on food stamps.’”

She corrected them, told them people can buy soda on food stamps.

Things like that kept happening. It was so disappointing, because this was where she was supposed to belong, but the people clearly didn’t understand her. She started thinking that maybe she identified with her hometown more than she’d realized.

Returning to her roots

This semester Funk is taking a class called Chemistry in Context. It’s all about seeing environmental science play out in the real world, so of course fracking came up. Fracking is personal for Funk, because her mom leased her family’s land to Chevron for fracking and the income has been a huge help.

In the class, some of the other students were talking about how terrible fracking was, about how it could ruin the water supply, and about the poor people who live near it.

Funk muttered under her breath while the other students talked about fracking and how it needed to be banned. She didn't speak up because she’d feel like a hypocrite, since the talking points her fellow students rattled off were all arguments she’d made herself over the years. It wasn’t that she disagreed in principle, it was that she didn’t like the way her classmates talked about a place where they hadn’t lived and about people they hadn’t met -- like her family, her neighbors.

“I didn’t want to be around these people that were talking about my home like it was some…different place where people are victims,” she said.

“I wanted to show there was power from the towns themselves. I wanted to be around people who were like me, and had that similar experience growing up.”

After all that, after leaving Mount Pleasant, for what she thought was for good, Funk wants to go home. And it’s the issues that drove her away to begin with that are making her want to return to Mount Pleasant.

Because she feels like that’s where there’s work to be done, where there’s a reckoning to be had over climate change, not in a place like Wellesley where everyone is removed, and for the most part agrees with each other.

But instead, in a town where hills are made of coal debris and people need fracking dollars just to get by. Where the conversations about this are messy, and that’s the point.

And so, nothing certain, but Funk’s plan is to double back. She’ll be able to pick up a lot of things where she left off, including her lawsuit. After the first one was tossed -- there’s been some revisions.

They’ve filed it again. Ashley Funk’s a plaintiff this time too.

Heat of the Moment is a long-term project about climate change, led by WBEZ Chicago.

to WBEZ

to WBEZ