Haz clic aquí para la versión en español - Click here for the video version

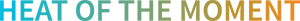

Noel and Alcaldio Martinez are two brothers in a family of 15. Noel is number 7, Alcaldio number 3. The brothers are close and talk on the phone almost every day. Lately, because of persistent drought in their home country of Honduras, they've been having the same conversation over and over again: whether it's better to leave or better to stay in Honduras.

So far they’ve made opposite choices. Alcaldio stayed, Noel left.

I first met Noel Martinez at work in New Orleans, remodeling a basement apartment in Broadmoor, a neighborhood some thought better to abandon after Hurricane Katrina. He and three other men were working on a day when most people went home early because of flooding.

A river of moisture from Central America that meteorologists nicknamed the “Mayan Express” had been hosing down New Orleans with rain. When I asked why the men opted to work in such terrible weather, they told me they don’t rest for this kind of weather. Noel chimed in from the stairs.

“[In Honduras], there isn’t work because there isn’t enough rain,” Noel spoke with me in Spanish about his home country.

Not enough rain, for a long time now. That’s why he’s here.

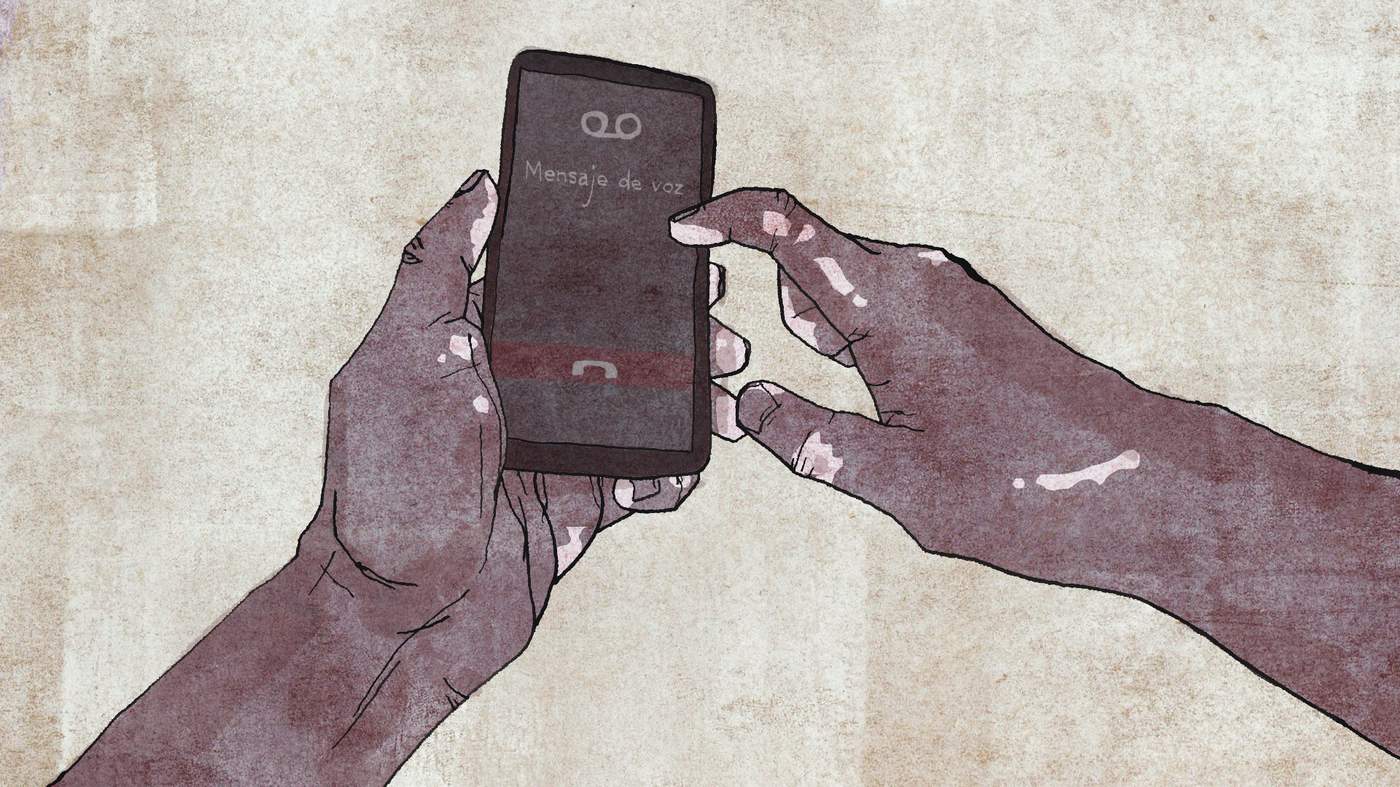

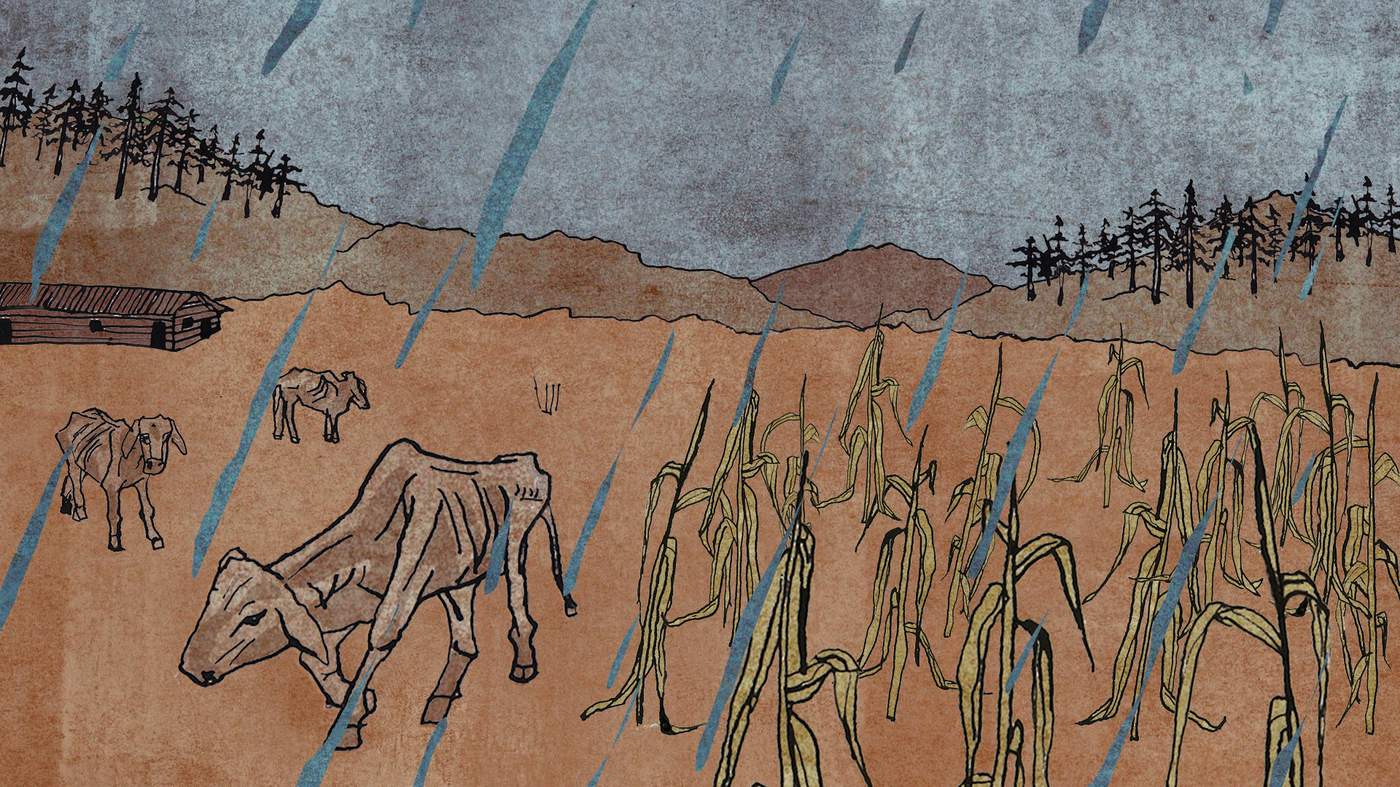

Noel and his brother Alcaldio grew up in a tiny town in the Central Honduran state of Yoro, surrounded by big pine tree forests. Every year, people there wait for the May rains to plant their fields and feed their animals. And when the rains do come to Yoro, people say it rains so hard, it rains fish. They post cell phone videos online to try and prove it really happens — children celebrate in the bright red mud holding tiny fish in their hands.

But for the last four years and counting, it’s been abnormally dry — and not just in Yoro. Across Central America, less rain has been falling later in the season. High temperatures have been breaking records. Staple crops like corn and beans and exports like coffee and bananas have been failing from fungus, pests and drought.

The pattern is precisely what climate change models predict for the region as global temperatures rise. It’s what drove Noel and Alcaldio to make different bets — to cross the border to the U.S. in search of work, or to wait out the weird weather and drought in Honduras.

Noel's choice

Being in the U.S. wasn't Noel's first choice. He borrowed from the bank to buy pesticides for his fields, but when the May rains didn’t come, he lost the crops anyway, along with the money. So he sold the farm and moved north to the city to cut palms. But the work didn’t pay enough to support his family, so after five years of deliberating, Noel opted to go even further north to an entirely foreign city.

“Everything that’s grown you lose,” he said. “That’s when you make the decision of risking everything and coming to [the U.S.] illegally.”

As Noel crossed the border, Alcaldio stayed back because he still had a job. He was a milkman at a dairy, a job that is supposed to be more stable than farming from one season to the next. But things were tough in Honduras. Another brother, who also stayed, was murdered.

“He was a farmer, and they just stole what he had on him and killed him,” Noel said. “All of this leads people to crime, I don’t know, as a way of making easy money.”

Noel got the news while he was still crossing the border and wanted to turn back and go home for the funeral. But his family told him to keep going — both the drought and violence in Yoro were getting worse. The Dry Corridor that spans Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador in Central America had been quietly expanding its boundaries and pushing rural farmers just like Noel into bankruptcy and starvation. Today, an estimated 3.5 million people don’t have food and twice that many are out of work.

You’ve probably heard a lot about Central American migrants — children crossing the border alone, families moving in record numbers. You’ve probably also heard people say they are refugees from violence, and they are. But violence and the drought that brought Noel aren’t entirely separate. Because droughts put so many out of work, research — even from the Department of Defense — tells us climate change undermines security. Desperate people turn to crime, turn on each other, turn to other countries.

People who flee weather or drought can't legally claim refugee status. If they are fleeing violence, however, they can — so that's what people list in immigration documents; it's what gets documented.

But beneath it all, climate is an invisible but constant force.

Alone in NOLA

Noel moved to New Orleans two and a half years ago hoping for a better life. But these days, he spends most of his time yearning for home. He remodels empty houses for 12 — sometimes 14 hours a day — those days are long and lonely. He hasn’t seen his five children or his wife since he got in the car and left them behind three years ago.

“You don’t know when you’re going to see them again,” he said. “It’s really hard.”

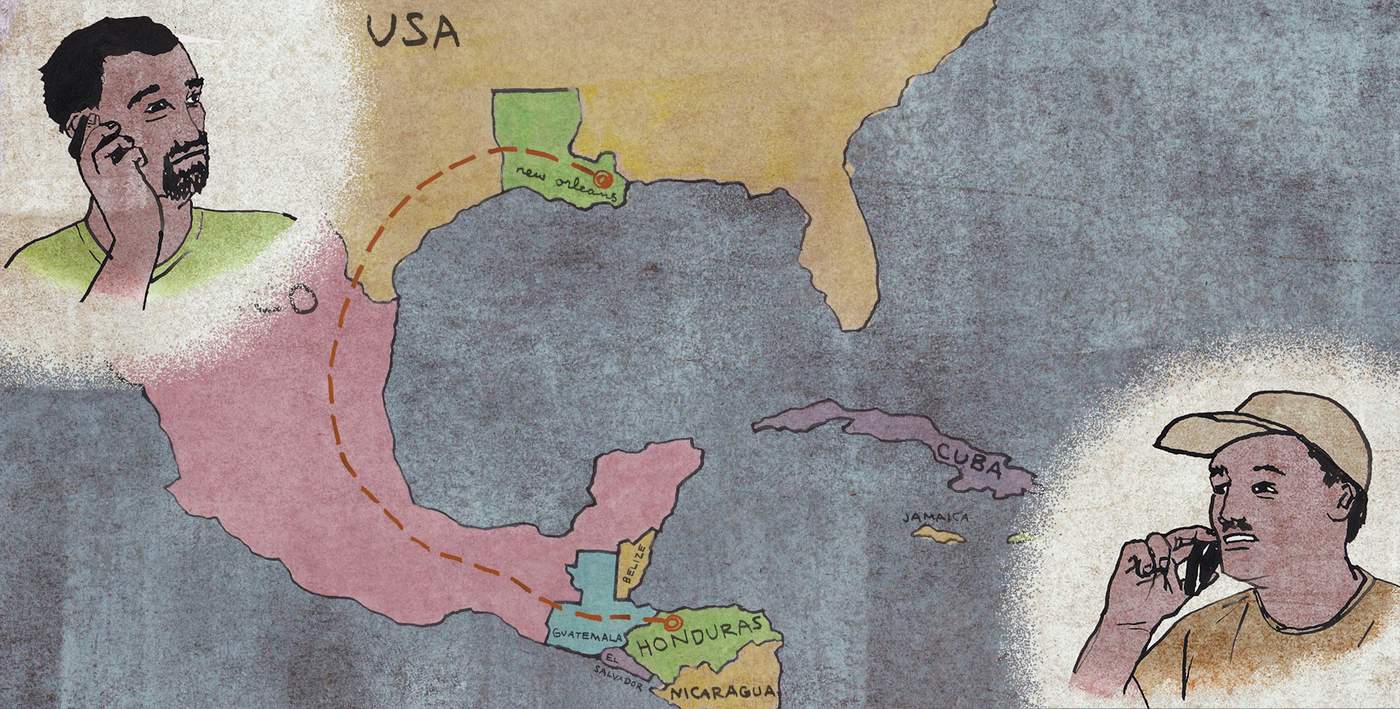

Alone in his apartment, Noel’s only lifeline to his family is his cell phone. With a paint encrusted finger he plays voicemails from his youngest daughters, ages 3 and 8. They heard that Dad hurt his hand on a drill, so they tell him to come home so they can heal him.

Noel doesn’t want to live like this, raising his family with a cell phone. He has plans to go back some day, but it’s hard to make the leap now that everyone's dependent on the money he is making here. This is what Noel keeps telling Alcaldio: supporting the family here, means risking never seeing them again there.

Dry times

Despite hearing all about Noel’s life in New Orleans — the loneliness, the dusk to dawn work, how much Noel misses home life in Honduras — Alcaldio now says he wants to come.

“He’s been asking me non-stop to help him come here,” Noel said. “I told him: ‘Let’s wait. I’m going to see how things are.’”

Alcaldio isn’t just missing his brother. Last year, the dairy where Alcaldio was working fired everybody. Without rain there’s no pasture, so the cows were starving. The ranch owner had no other option but to sell the cows for meat.

In 2016, things got more dire. Fires raged as controlled agricultural burns got out of control. The smoke kept international flights from landing at the airport. By April, the only work Alcaldio could find was guarding wood in the lumber yards, a job created by extreme heat. It caused Southern bark beetle populations to explode; they devoured all the pine tree forests across Honduras. The only way to stop the beetles is to cut down the trees and use them for lumber. The town even called in the Honduran government to help.

Growing up, Noel said he always looked up to his confident older brother — on the soccer field as well as the farm fields. But now it’s Alcaldio looking to Noel for confidence as the Honduran heat erodes it.

Noel urged him to be patient: Wait. What if the May rains come?

Alcaldio's choice

By April, people in Noel and Alcaldio’s hometown had begun to ration water: two hours in the morning, two hours at night. But there was still not enough to fill their tanks. Alcaldio and his neighbors were losing hope. But then something happened that surprised and delighted the town: the May rains came early.

“The land got wet and we got happy because it calmed the dust,” Alcaldio said, also speaking in Spanish. “It cleared the smoke in the air. The animals that were sad from thirst and heat, got happy as well.”

With three more rains, he said, the jobs everybody lost would start coming back.

But while the rain might have changed Alcaldio’s job prospects, it still hasn’t changed his decision to come to the U.S.

The lumber Alcaldio has been guarding had him thinking hard about the future — it came from pine trees that are essential to cooling the region and to longer-term rain patterns. Alcaldio doesn’t have a doctorate and he’s never heard about climate change, but he knows his hometown and the difference between today’s weather and tomorrow’s climate. A single storm, this one season’s sigh of relief, can’t erase the longer-term risks of living in an unpredictable climate.

Now the pine trees are gone — thanks to beetles and extreme heat — and Alcaldio worries his hometown is becoming a desert.

“In the desert there are no trees, everything is barren, there is no shade...no deer, no snakes, no birds, no other animals, it’s like nature is no longer there. It’s destroyed.”

To survive, Alcaldio says he needs to migrate, just like the animals already have. His wife doesn’t like it, his four kids don’t like it, but he says it’s what he needs to do to support them. He plans to leave them with 3,000 lempira in hand — about $150 — until he makes it across the border. In the meantime, he’s spending as much time as he can with his youngest son.

“He’s already a year and a half old and he knows me. I take him for rides on our motorbike and when I’m not there he cries,” Alcaldio said. “He is going to miss me a lot, but it’s a decision I made as a way to move forward, so he has to get used to being with his mom and brothers.”

Here or there?

Back in New Orleans, Noel still dreams about returning to Honduras. In seven years, he says, he plans to buy a house again. His wife thinks he’ll never come back.

Still, Noel works hard to stay connected — when the kids come home from class and want to watch TV instead of talk, he sends videos of the storms in New Orleans.

“I sent a video showing them, ‘Look how much it’s raining!’ And my wife says, ‘Here we can’t even bear this heat anymore, we’re burning. It’s very hot.’”

There’s the illusion that a right choice can be made here, one that will make the two brothers happy, make their family happy. But as they eye each other across the border, as much as they can see all the ways the other one got it right, they can also see all the ways the the other one got it wrong.

Any choice comes with a cost. Floods one place. Drought another. Loneliness here. Poverty there.

As the climate changes, Noel, Alcaldio, and all of us are in a new world of decision risk. We don't know how our choices will play out, so we place bets. Raise kids, pay mortgages, change jobs, or move on. We do what we can, and hope for the best.

Translations by Marina Colorado and Mariana Martinez

Voice-overs by Juan Castaneda and Luis Antonio Perez

This story was produced in collaboration with iSeeChange, a community climate and weather journal.

to WBEZ

to WBEZ